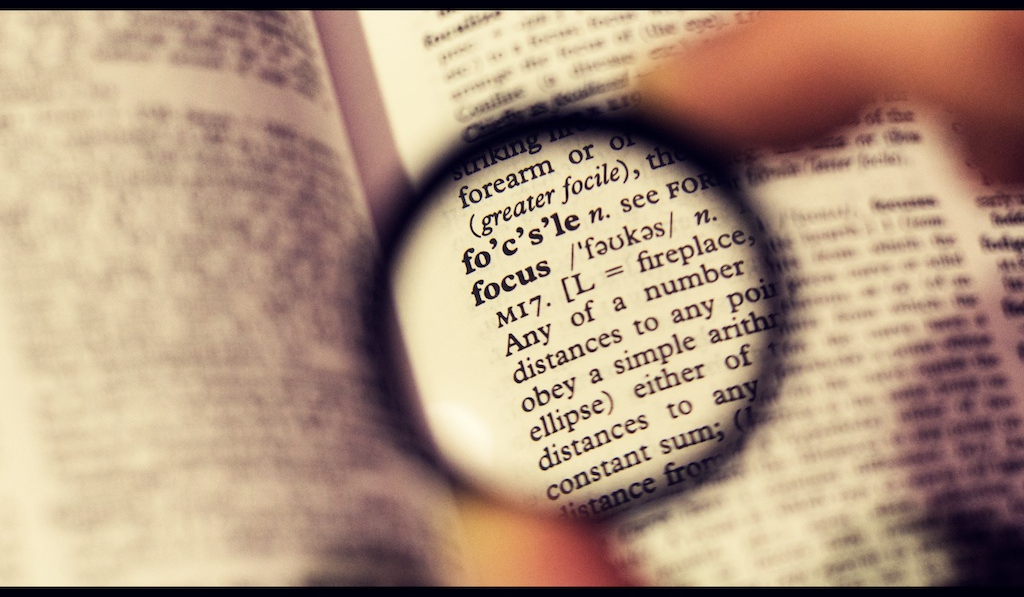

Photo by Michael Dales

I’m naturally very distractible and messy – a “big-picture thinker, but not so much a detail person,” as my father would euphemize when I was younger. I’m often tempted to work on a lot of things at once, inefficiently, and without finishing much. This tendency can wreak havoc on my ability to get anything done as a writer.

I work from home most of the time, so the pull of all the things that I could be doing instead of writing is usually more powerful than any intention I have to just focus.

(Some of the things that tempted me this morning: the laundry, the breakfast dishes that didn’t fit in the dishwasher, chatting with my neighbor, retrieving the dog’s ball from behind the sofa so he stopped barking at it, e-mail, texts, a quick thank-you note, bills, yesterday’s mail, and chatting with my husband on the phone.)

I had to carefully construct a work structure for myself that would support focus rather than allow me to hop from one easy but not important task to another.

Forcing myself to stop multitasking was a process. I had to create a formal ritual to get myself into the zone. Here it is:

As I’m brewing myself a second cup of coffee or tea, I take a quick peek at my calendar and e-mail on my phone. Is there anything urgent? The idea isn’t to respond to e-mails; it’s a check that keeps me from worrying while I write that I should have checked my e-mail, and keeps me from wondering if there is anything on my calendar that I should be preparing for. Then I head to my office, with my coffee and a full glass of water. (I’ve also had a snack and used the restroom. I’m like a toddler going on a car trip.)

I do a quick cleanup, removing yesterday’s coffee cup from my desk, closing books left open, putting pens back in their place. I put all visual clutter in deceivingly neat piles. I put my phone in do-not-disturb mode, and close any unnecessary applications or windows that are open on my computer. I launch Pandora and choose the “listen while writing” radio station I’ve created (mostly classical piano because it doesn’t distract me like music with lyrics does). I tell Buster, my trusty canine colleague, to go to his “place” – a bed right next to me where he’s trained to stay while I work.

I write at a standing desk that has a small treadmill under it. When I’m ready to start writing, I start the treadmill. Walking slowly while I work has a lot of positive outcomes; one of them is that it more or less chains me to my desk. Finally, I launch the app 30/30, which times my writing and break time.

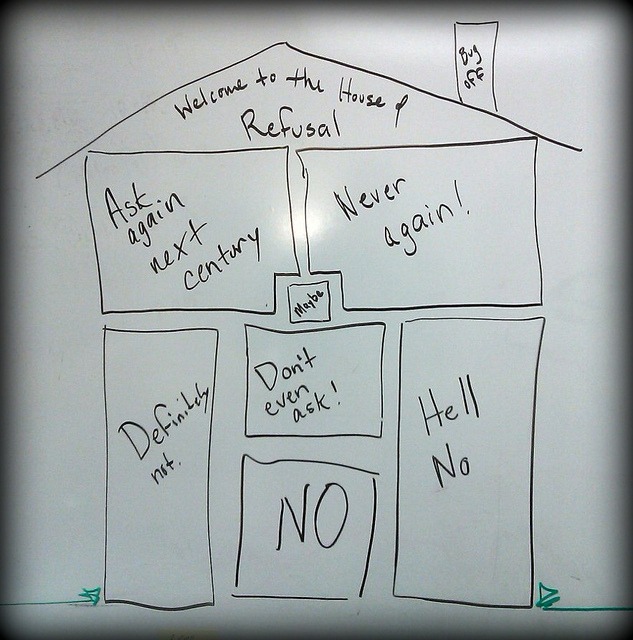

At first, I actually felt guilty for carving out such dedicated time to focus on my writing. Perhaps that sounds ridiculous to you – it’s my job, after all! But honestly, I felt like I should be more responsive to my colleagues’ e-mails throughout the day, and I shouldn’t be creating the scheduling nightmares that blocking off dedicated work time does because it’s basically at the same time every day. It’s very hard to schedule a meeting with me in the morning, when I do my best writing, or in the afternoon, when I pick up my children from school. This means that it’s pretty hard to get me to go to a meeting.

So how did I ultimately let go of the guilt? Instead of trying to conform to the norms of the ideal office worker (which made me feel a little terrified anytime I was straying from that path), I started to see myself as an artist. I read everything I could about other writers’ and artists’ work habits, and talked to a half dozen successful writers about how they get things done. Guess what?

They have writing rituals just like the one that I set up. Seeing myself as a part of their tribe made the whole thing easier for the part of me that is people pleasing and wanting to conform with what people see as hard-working.

Do you struggle to block off dedicated time to write? If so, I welcome you to join my tribe.