Dear Christine,

I know you have teenage daughters around the same age, so I’m hoping you have some insight about how to help kids deal with stress. My youngest daughter has always been confident, gregarious, and goal-oriented. But starting in her sophomore year in high school, she’s not been herself. She’s stressed and bitchy with us, and suffers from general malaise. She’s had a lot of stomachaches and headaches and was even experiencing hair loss, so we took her to the pediatrician and then a specialist to make sure she didn’t have an underlying medical problem. She doesn’t. The doctors say her symptoms are due to stress.

As a family, we try to keep things mellow, upbeat, and relaxed. We don’t put pressure on her to perform or achieve. She goes to therapy, and we are in close contact with her doctors. But, still, she is not herself. I understand that she cares a lot about her grades and schoolwork, but to be totally honest, I’m not really sure what she’s so stressed about.

How can I get my daughter back?

Thank you,

Pulling Out My Own Hair

Dear Hair-Puller,

Your daughter is not alone. A recent survey by the American Psychological Association found that fewer than half of her generation would rate their own mental health as “excellent” or “very good.” And it doesn’t seem to get better as they get older; more than 90 percent of today’s 18 to 21 year olds experienced at least one physical or emotional symptom due to stress in the past month (this is very high compared to other adults). In addition to the physical symptoms your daughter is experiencing, other common symptoms of stress include feeling depressed or sad, showing a lack of interest in school or their daily lives, lacking motivation or energy, and feeling nervous or anxious.

What seems to be new about today’s teenagers is that they aren’t just stressed about what’s going on at home or at school or in their own lives—they’re stressed about the world they are living in. For example, three quarters say they are stressed about mass and school shootings. More than half feel stressed about the current political climate, and more than two-thirds feel significantly stressed about our nation’s future. About 60 percent are worried about the rise in suicide rates, about climate change and global warming, and about the separation and deportation of immigrant and migrant families. The list goes on and on and on.

It’s no wonder that our teens are suffering. Fortunately, there is a lot that we can do for our stressed-out teens. You’ve already done a couple of important things: You’ve taken your daughter to the doctor and gotten her into therapy. Professional help is always a great place to start.

What else can we do? I’ve taken a lot of advice on this topic from Lisa Damour, who has a relevant new book out called Under Pressure: Confronting the Epidemic of Stress and Anxiety in Girls. If you are looking for a comprehensive guide to helping girls cope with stress, this book is the best one I’ve read. Here are three steps to helping teens cope.

1. First, just listen

Ask them to describe the difficult circumstance that is stressing them out. Maybe it is a problematic friendship; perhaps they didn’t make a team they really wanted to be on.

At this stage, acknowledge that their difficulties are real—even if they sorta seem dramatic or overblown or irrational. The key is not to deny what they are going through and how it is making them feel (e.g., by saying something like, “But you have so many friends!” when they say that they are lonely). Instead, have them simply give you the facts of the hard place they are in, and, in response, show calm curiosity about their experience. The goal is not to take away their pain. The goal is for them to feel seen and heard by you.

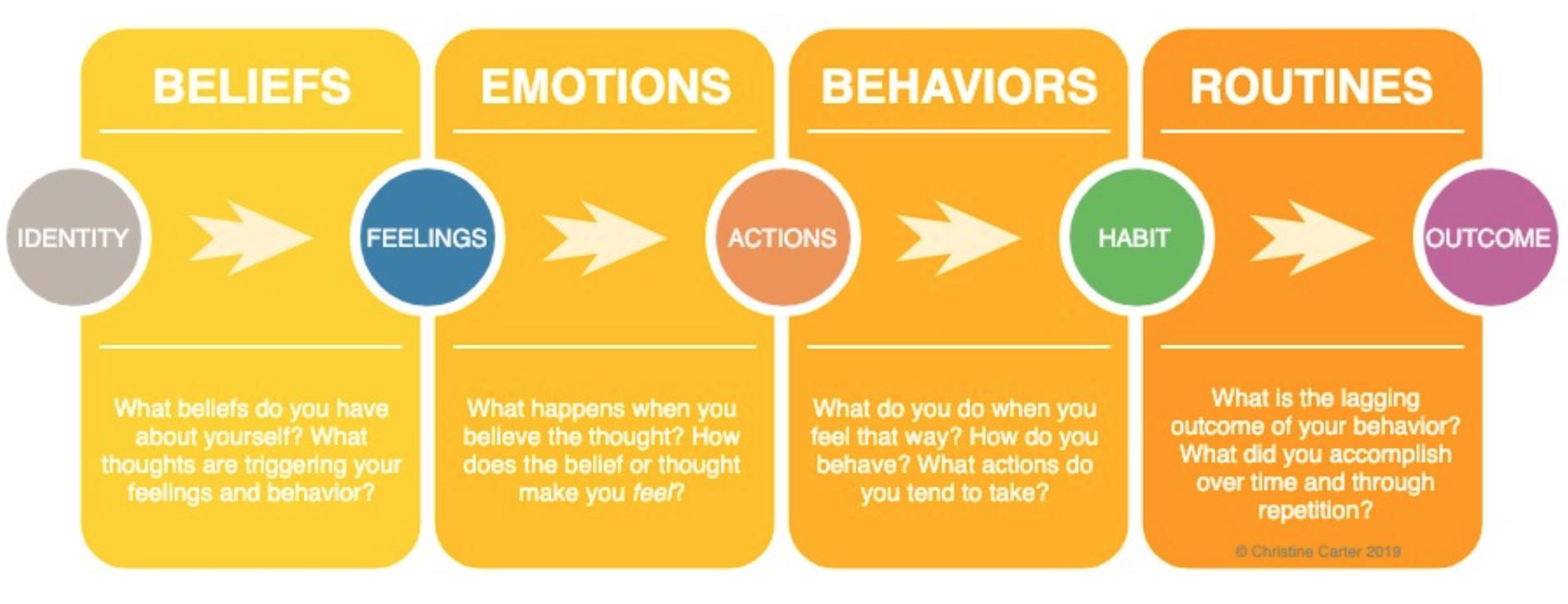

Second, help them identify how they are feeling in response to the stressor. “I’m feeling anxious right now,” they might say, or “I feel stressed and nervous.” This is the “name it to tame it” technique; research shows that when we label our emotions, we are better able to integrate them. If they start telling you a story that is making them more emotional, gently bring them back to what they are feeling. The task here is to identify WHAT they are feeling, not necessarily WHY they are feeling that way. This can be hard; we get attached to our narratives about why we are upset. It’s usually easier to stick to our story than it is to reveal how we are feeling. But again, the task here is to talk about the actual emotions, not the reasons for the emotions.

See if you can sum up their stressful experience or circumstance (the facts, not the story) and their feelings about the circumstance in a simple phrase or two. For example, “You didn’t know how to solve five questions on your math test today, and you are feeling really scared that your grade is going to drop in that class.” Throw in a little empathy if you feel like you need to say something else: “That’s so hard. I can remember some very difficult math tests when I was in high school, too. It’s awful.”

Again: Resist the urge to give advice, make suggestions for how they can fix the problem, or offer platitudes like “This too shall pass.” You do not need to offer reassurance. Really. Right now, teens need to feel heard, and if you say something along the lines of “Everything will be okay” or offer specific reassurance like “Even if you fail the test, you’ll still probably have an A- average,” they’ll notice that you’ve missed the main thing they are trying to communicate, which is that they are very stressed out.

The other goal here is to show them that you are not anxious about their anxiety; you accept it. This helps them drop their resistance to the stressor. Why? Because resisting the current reality doesn’t help us recover, learn, grow, or feel better—it just amplifies the difficult emotions we are feeling. There is real truth to the old aphorism that what we resist persists; weirdly, resistance prolongs our pain and difficulty.

The more our kids resist reality, the more likely it is that they will start showing signs of a dysregulated stress response. In other words, when kids aren’t managing stressful or difficult situations effectively, they tend to start having larger and larger stress responses to smaller and smaller stimuli.

2. Encourage them to diagnose their stress

Damour’s stance is that we parents are most useful to our teenagers when we help them ask themselves: “What is the source of my stress?” and “Why am I anxious?” It might be obvious to you what is going on; the task here isn’t to hand them a diagnosis but, rather, to help them see for themselves what is going on more clearly.

It can help to let kids know what stresses most people out. Sonia Lupien at the Centre for Studies on Human Stress has a convenient acronym for what makes life stressful: NUTS.

Novelty

Unpredictability

Threat to the ego

Sense of control

We can help our kids identify causes of stress by looking for what might be new or changing in their life; looking for sources of unpredictability; identifying ways that their competence or safety is being threatened; and asking about the things in their lives that feel out of their control.

In addition to searching for sources of stress, it can be helpful for teens to classify the particular strain of stress they are experiencing: Is it related to a negative life event? Is it the result of cumulative day-to-day difficulties that are beyond the teen’s control?

Life-event stressors are things like the death of a loved one, or changing schools, or dealing with your parent’s divorce. The more change a life event requires a teen to make, the more stressful it will tend to be.

Chronic stress is when “basic life circumstances are persistently difficult,” according to Damour. Chronic stress is caused by things like living in poverty or living with a severely depressed parent, or having a chronic illness like cancer. I also suspect that many of today’s teens are experiencing a form of chronic stress caused by current events—global warming, rising suicide rates, mass shootings, etc. And social media is a source of chronic stress for many teens; nearly half say social media makes them feel judged, and more than a third report feeling bad about themselves as a result of social media use.

Surprisingly, one study found that the number of daily hassles a teen faces can predict their emotional distress over time, and that daily hassles have a greater impact on teens’ well-being than other types of stress. Daily hassles are often related to negative life events and chronic stressors, of course—a death in the family, for example, can create a mountain of hassle.

Surprisingly, daily hassles tend to be more distressing for teens than negative life events or chronic stress. Knowing this, often we can help kids solve some of their daily hassles, even if we can’t change their circumstances.

For example, last year one of my teenage daughters was going through a really hard time at school socially, and she was having some minor but persistent health problems. She also had a daily hassle: getting home from school. She had to walk 1.2 miles to her bus stop, and she was often waiting, sometimes in the rain, for 40 minutes or more for the bus to come. This was precious homework time. She was super stressed and having a hard time keeping up in her classes. I couldn’t ease her social pain or fix her health (both chronic stressors), but we eliminated the daily hassle of getting her home from school—the straw that was breaking the camel’s back—by creating a carpool.

3. Finally, help them see where their stress is healthy

It can help teens to teach them the difference between stress and anxiety. Stress, according to Damour, is the tension or strain we feel when we are pushed outside of our comfort zones. Stress is healthy and helpful when it creates enough tension and strain to foster growth.

Think of a muscle that is stressed by weight training: It tenses up and even breaks down a little. The weight might be very hard to lift, and the muscle might be sore afterwards. But the stress of a heavy weight—so long as it isn’t so heavy it causes a significant injury—strengthens the muscle.

Stress can work the same way. School is supposed to be stressful in this way. A mountain of research shows that we learn and grow when we are out of our comfort zone—when we are exposed to novel challenges. Stress can act like a vaccine for future stress (researchers call this “stress inoculation.”) People who are able to weather stressful circumstances frequently go on to demonstrate above-average resilience.

Anxiety, on the other hand, is the fear and dread and panic that can come up for us in the face of a stressor (or even just the mere thought of a stressor).

Sometimes anxiety is an important warning system that we are in danger. It’s appropriate for us to feel anxious when we are a riding in a car where the driver is texting, for example. Legitimate anxiety makes us want to get the heck out of whatever situation we are in. I once had a really nice-seeming neighbor who scared the bejeezus out of me. Every time he’d stop to chat, friendly and normal-seeming as he was, the hair on my neck would stand up, and my heart would start racing and thudding in my chest. It was all I could do to not run and hide from him. It turns out that my anxiety was legitimate: I later found out that he had spent a decade in a maximum-security prison for violent sex crimes.

And sometimes anxiety is more about excitement than it is a sign of danger. As Maria Shriver writes in And One More Thing Before You Go, often “anxiety is a glimpse of your own daring . . . part of your agitation is just excitement about what you’re getting ready to accomplish. Whatever you’re afraid of—that is the very thing you should try to do.”

But more often than not, our anxiety isn’t helpful. Unhelpful anxiety makes us hesitate rather than bolt. We are afraid of looking stupid, and so we don’t ask a burning question. We fear failing, and so we don’t even try.

We can help our teens figure out whether they are experiencing legitimate anxiety or unhelpful anxiety. Do they have the desire to get the heck out of whatever situation is making them anxious and afraid? If so, their anxiety is likely legitimate. We can support them in getting out of that dangerous situation.

But if their anxiety is making them hesitate, help them consider that their anxiety is unfounded—and that it is holding them back.

All of this requires trust, Hair-Puller. Trust that if our teens are still here, still breathing, everything is actually okay. Trust that even if we don’t immediately fix everything, life will continue to unfold just as it’s meant to. Trust that even if it all goes to hell, even if other people make mistakes or do things differently than we would do them, our kids can deal with the outcome. Trust that they (and we) can handle all the difficult emotions that come up in response to what does or does not happen.

When we accept the reality of a stressful or scary situation and our limited control, it allows our kids to do the same. Importantly, our acceptance also frees them up to move forward, rather than remaining paralyzed by stress and anxiety.

Yours,

Christine

In Dear Christine, sociologist and coach Christine Carter responds to your questions about marriage, parenting, happiness, work, family, and, well, life.

Sign up for Christine’s monthly email list (that’s right: it’s only one email per month) to receive notifications of new columns. Want to submit a question? Email advice@christinecarter.flywheelsites.com.